The U.S. is taking the trade fight to the front door of Fortress China, a step that could hold more promise for companies than the endless debate over the value of the yuan.

Prodded by corporate chiefs across the country, U.S. trade officials have launched a coordinated attack on the core of America's commercial conflict with China: the heavily protected and subsidized Chinese state-owned enterprises that are pounding U.S. companies not just in China but in competition globally.

"There's been a change" in the U.S. approach to Chinese state capitalism, says Christian Murck, who heads the American Chamber of Commerce in China, which represents U.S. firms. "It's a good change."

"It's something of a paradigm shift," adds John Neuffer of the Information Technology Industry Council, whose corporate members have been hit hard by China's policies. "China is giving a leg up to domestic producers that we think is discriminatory to foreign companies—that's what we're fighting across the board."

The heightened focus on Beijing's grip on the China market is long overdue and takes place—big surprise!—in an election year. The question is: What will the U.S. do besides jawbone?

And jawbone it has. In bully pulpits in Geneva, Hong Kong, Beijing and many other venues, top officials from the State Department, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and other agencies have sounded the alarm. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in New York that the U.S. wants "competitive neutrality" for world commerce and warned that state-owned enterprises enter global markets "not just for profit, but to build and exercise power on behalf of the state."

Robert Hormats, the State Department's top economic official, told a group of U.S. firms in Washington: "The trade distortions created by the 'China Model' are disadvantageous to our U.S. companies…and a direct threat to U.S. jobs and competitiveness." And he repeated the criticism in Beijing.

In Davos last month, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner described China's state capitalism and its "subsidies and distortions" as "very damaging" to trade partners, echoing comments made by President Obama in his State of the Union address.

"Increasingly, trade frictions with China can be traced to China's pursuit of industrial policies that rely on trade-distorting government actions to promote or protect China's state-owned enterprises and domestic industries," the U.S. Trade Representative told Congress in December.

Beijing rejects this criticism and says China is merely developing its economy the way others have theirs. It isn't lost on China that many other developing countries still have state owned enterprises, including Russia and Brazil. The U.S. has dabbled in the model as well.

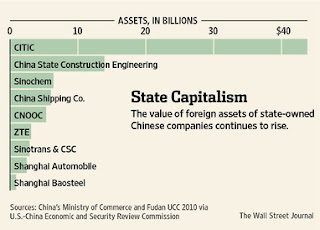

It is the omnipresence and girth of its SOEs that distinguish China. Supported by large state subsidies and preferential financing, taxes and regulations, the SOEs are at the center of China's drive for "indigenous innovation." They also empower the Communist Party leadership, which controls the national SOEs and their thousands of subsidiaries and related entities.

That vast empire accounts for about half of China's nonagricultural GDP, says the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which reports to Congress.

So when a U.S. company goes to China to compete with a Chinese company, it often finds itself competing instead with the state. And it is the state that has the handy advantage of approving or rejecting the foreigner's investment, or demanding the newcomer transfer technology to China before getting access.

If you can't beat them, join them, which is what many companies—GM, Volkswagen and General Electric among them—have done by joint venturing with a Chinese SOE. The Chinese giants also have invested outside China, including in the U.S. Backed by the government's big subsidies, they often underbid U.S. and other competitors for international contracts, sometimes using the technology they got in one of those joint ventures.

In its new five-year plan, China goes further, identifying critical new industries the state plans to dominate and setting aside hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies to fund that mission.

"If anything, China is doubling down and giving SOEs a more prominent role," says the Review Commission.

So what to do?

U.S. companies won't talk on the record about troubles in China because they fear retaliation. Increasingly, though, some top executives have wondered aloud whether the U.S. itself needs more government-led industrial policy.

Trade experts say new trade agreements, such as the evolving Trans-Pacific Partnership, will create trade clubs with enhanced market access but stricter restraints on state enterprises. The message to China: If you want to join, you have to change. But China Inc. knows its huge market will continue to attract investment. It may simply say, "No thanks."

Others suggest that a bilateral investment treaty between the U.S. and China could offer enough incentives to entice China to liberalize faster. But the incentives would have to be enormous to dislodge the politburo from its perch atop Chinese commerce.

"I don't have magic answers," the State Department's Mr. Hormats says. "But if they continue along these lines, they risk the global system turning inward, which will have very serious consequences for them."

An industry observer says no one wants a trade war, but a stick may work better than a carrot. "What we have the most control over is our own border and access to our own market," he says. "There's no way of addressing these issues without inflicting some pain on ourselves."

In the meantime, the U.S. is using a rhetorical battering ram on the fortress door. It's tough to see, though, how words alone will breach much of anything.

1 comment:

It is easy to see why the US is less than comfortable with the power currently held over trade with its state operated enterprises. It gives them a distinct advantage over private companies trying to compete with them. However, it is for this reason that there is very little that we can to to change this. Even international pressure probably won't be enough, and it won't be until the model is less profitable that China will consider change. Even with the suggested measures in the article, China probably would stand to make a lot more profit simply continuing its current practices.

Post a Comment